Usually the exchange is simple and cordial, and I’m back in my music before the plane is out of the gate. Today, I had a more interesting interaction on my forty-five minute flight between the Hawaiian Islands. The passenger next to me was a native Hawaiian – his name is Jon. The typical questions:

“How’s it going?… First time in Hawaii?… Here by yourself? Visiting family?…

“Oh, you’re here for work. What do you do for work?

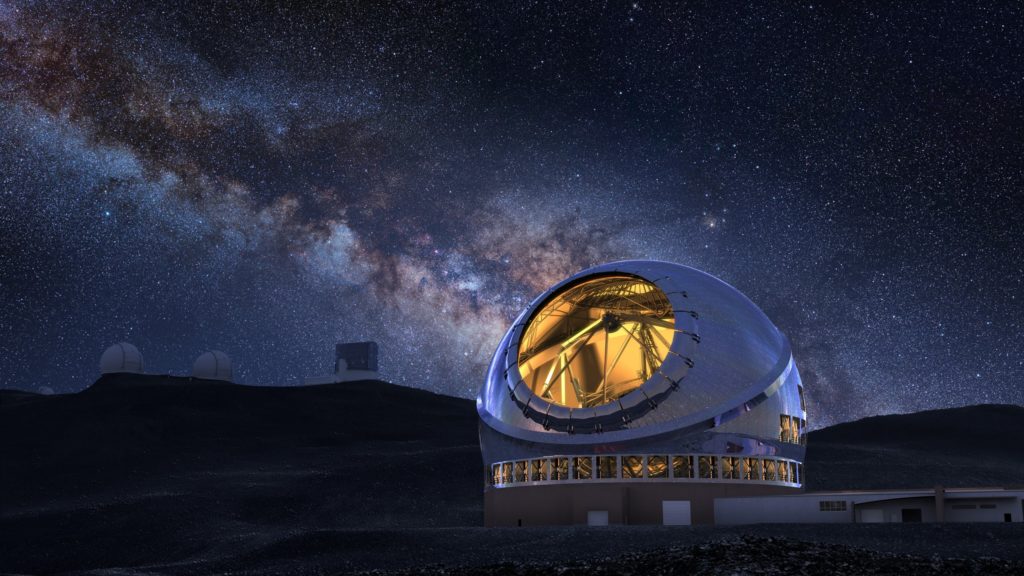

I love my job, so I’m usually enthusiastic about telling people that I’m an astronomer. Most people are excited by science and amazed at space – something I can easily utilize to initiate a fun and deep conversation. In Hawaii, though, many of the natives have recently been protesting the development of a new telescope, the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), and relations have gone to the point of violence and theft of observatory vehicles in a few cases. With these tensions, I was unusually uncomfortable giving away my career, but I did it anyways, hoping for no hard feelings. Jon seemed nice enough anyways.

Observatories on the volcanic summit of Mauna Kea, the highest point in the state of Hawaii and a sacred mountain in Hawaiian religion. (Image credit UH/IFA)

“Oh, you’re an astronomer… It’s interesting that we find ourselves sitting next to each other. I’m actually one of the main individuals fighting the development of the TMT in court.

Of all the people that I could be sitting next to… However, Jon remained friendly and interested to talk to me about the issues. In fact, he’s also a professor of History at University of Hawaii, specializing in Hawaiian culture and history. No wonder he’s on the side of the protestors, whose leading vocal outrage is at the use of their sacred and religious mountain for the big mechanical industry of astronomy.

But is that what it really is? Is astronomy really the same facet of human civilization that has enveloped some of the most beautiful places on our planet with concrete jungles – forever muddling the landscape with whatever structure we envision is more economical?

The Hawaiian Islands are a perfect example of this. As we flew over the islands from Oahu (where I previously had a connecting flight in Honolulu) to the big island of Hawaii, where the volcano and observatories are located, I asked Jon about the islands. The first was Molokai, as he pointed out, an island with an almost all-native Hawaiian population. Their rural communities and expansive farms were visible from the air, with pristine volcanic beaches with clear water on all sides. The natives work hard to keep it that way, a vestige of what Hawaii was, and not the tourist trap that we think of here on the mainland. They even had something to do with the disbanding of the ferry, which would have transported cars and people between the islands. Instead, people have to fly (or catch a ride on fishing vessels), and the cars are for the most part landlocked.

Next was Maui – in stark contrast to Molokai, as Jon put it “Maui seems to have accepted everything that modern Western culture has to offer.” Hotels line the beaches. Harbors abound. Cruise ships dock and deliver their passengers to their island ‘paradise’.

The island of Molokai on the left, largely untouched by tourism and modern megastructures, and the tourist-frequented island of Maui in contrast on the right. (Image credit tripadvisor.com)

After an American-led overthrowing of the Kingdom of Hawaii and subsequent illegal annexation of the Republic of Hawaii (which the US formally apologized for under the Bill Clinton administration), many natives are weary of big government and industry from the mainland. As one of the telescope operators described to me, the telescope protests are largely an issue of sovereignty. Jon, as many other natives, sees the development of the TMT, and all of astronomy in Hawaii, in exactly the same light – big industry from the mainland occupying their natural resources.

But as a scientist, that’s not how I see what we’re doing. Although it bears the similar appearance of the bulldozer and giant sheet metal, as I described to my new acquaintance, the goal is not to make money or to provide jobs, industry, etc. The goal is learning about the universe, and using modern technology to open a deeper understanding of where we are and where we come from – fundamental questions of the human condition.

“That’s a very interesting way of putting it.”

He was also succeeding in making me question the merit and methods of what I’m making a career and life obsession out of. Is it worth leveling the tops of mountains and installing gigantic metal structures, continuing to play into our self-assigned god-like role of shaping the planet for our own interests? And of the mountain’s sacred origin to the native Hawaiians, is it worth intruding on their most sacred places, essentially taking over their most holy landmark, simply because it is the best astronomical site on Earth? Is it possible for us as a global community to decide that the benefits outweigh the costs on an island so distant from most of us? Does that make it okay?

Although, not all Hawaiians are in opposition – in fact protests have been ongoing on both sides. Some Hawaiians, including the University of Hawaii, are in support of the new telescope. For the ancient Hawaiians, the necessity to navigate between the islands meant that they were among the most astronomically advanced civilizations before the development of the telescope. With that history, and with the best skies on Earth, it seems fitting that Hawaii should remain on the cutting edge of astronomy – necessitating big telescopes in the era of extremely large optical telescopes.

I have to settle in favor of astronomy. Although I could easily seek another career, higher paying than academia no doubt, I have stronger reasons for what I’m doing. I think that most of astronomy has benevolent motivations. My own research as part of Project EOS is aimed at unraveling the questions of how planets form and what types of planetary systems are out there. In the near future, this groundwork that many others and I are working on will guide our search for simple forms of alien life on other planets, and possibly even for other planets that humans could travel to and inhabit – something that may be necessary for our continued survival. Without big telescopes in the sites with the best atmospheric conditions on the ground, this research simply isn’t feasible.

“Oh, you’re interested in finding out how planets form! Well, it’s really difficult for me to tell you I don’t want you to do that.”

Our conversation seemed to be wrapping up, and so was our flight. We landed in Hilo, and I drove to the summit of Mauna Kea where I would be staying for a few days centered on my allotted time on NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility.

NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility on the summit of Mauna Kea, where I would be observing planet-forming disks of gas and dust around young stars.

I had a built in buffer day in case something went wrong with travel, and to get acclimated to the high altitude before actually having to observe. Since things went smoothly, I went out exploring the first day. Across from the astronomers housing are a few hills (that turned out to be individual volcanic caldera) with trails leading up them, and rock piles visible on their summits. Being used to hiking desert trails, I know a cairn when I see one. This was the biggest cairn I had seen, and I headed up the steep and lightly beaten trail up to it.

When I got there, I found something that I didn’t expect. Instead of a pile of rocks to mark the trail, or a cool viewpoint, I found a shrine and a tomb. There were small tributes among the rock pile – native grasses strewn into a necklace, particularly aesthetic rocks, even a seashell filled with rolled up human hair. The latter was admittedly strange to me, but in another light I see it was a beautiful tribute by someone who deeply loved the person who was buried beneath the rocks.

I continued on through seemingly endless rock piles. They literally covered the mountainside. The whole place was entirely peaceful, though sullen. Wildflowers peppered the sides of the trail, and an ominous fog descended on the mountain. Feeling like a stranger here, I decided it was time to leave.

When I returned to my room, I researched and affirmed my suspicions that the piles of rocks are native Hawaiian graves. I felt a little remorseful for having entered this realm, but I was respectful and admiring of their culture, and glad that I had a chance to glimpse into their world. I understood why the natives have such a high respect for the mountain and feel the need to protect their heritage and identity.

While reading about the rock graves, I came across a description of the sacred nature of the mountain. In Hawaiian religion, the mountain summits are “places of gods for men”. Their summits are where the people would pilgrimage to seek a connection with the heavens to inform their earthly lives. In the same light, I see astronomy as the pursuit that seeks lessons gained from the heavens to inform our lives and actions on Earth. Though I can’t claim that Mauna Kea is “my mountain” in any right, I think that astronomers are utilizing the mountain in its most sacred sense – a connecting point between heaven and Earth, where observers seek and telescopes collect the lessons of the heavens.