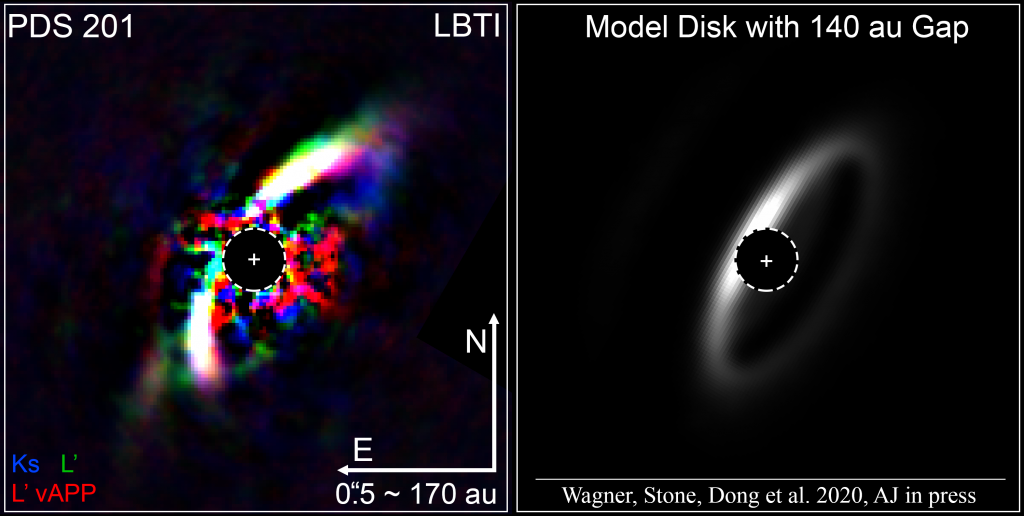

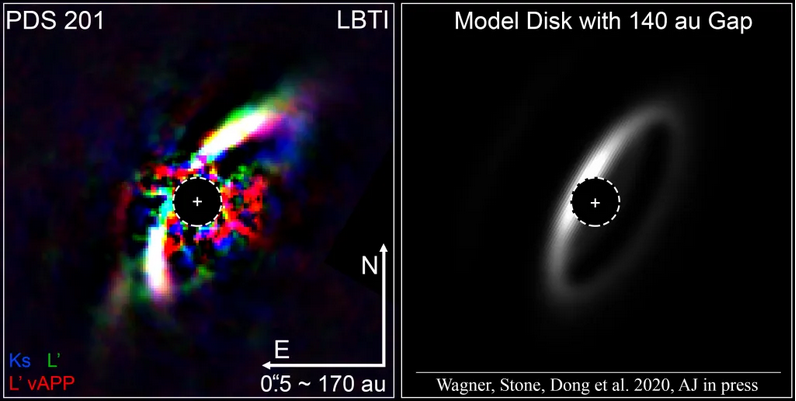

Protoplanetary disks offer an opportunity to learn about the processes by which planetary systems form and evolve. Images of these young systems also enable us to study, by analogy, the formation of our own Solar System, in which the common orbital plane of the planets evinces the primordial orientation of the disk from which our system formed. Images of a few dozen protoplanetary disks form a collective scrapbook that can be organized by stars of different mass, age, etc. to uncover trends in the planet formation process. In this context, images of each new system add an important, and often unexpected, piece of the puzzle. PDS 201 is one such disk, of which we excitedly obtained the first images during an observing program led by EOS scientists Kevin Wagner, Daniel Apai, and Joan Najita.

Encircling a young star in Orion that is roughly twice as massive as our Sun, the disk around PDS 201 is remarkably large: extending to hundreds of astronomical units from the star, and showing a wide gap in the central regions that is probable evidence of a forming planetary system. What makes this disk particularly exciting is that its central gap is so wide that the planetary system hiding within could likely be among the most massive that we’ve uncovered yet! Our EOS team is continuing to observe PDS 201, with the goals of learning more about the disk environment and looking for the young planets in its interior. More details about the disk around PDS 201 can be found in our recently accepted paper in the Astronomical Journal.